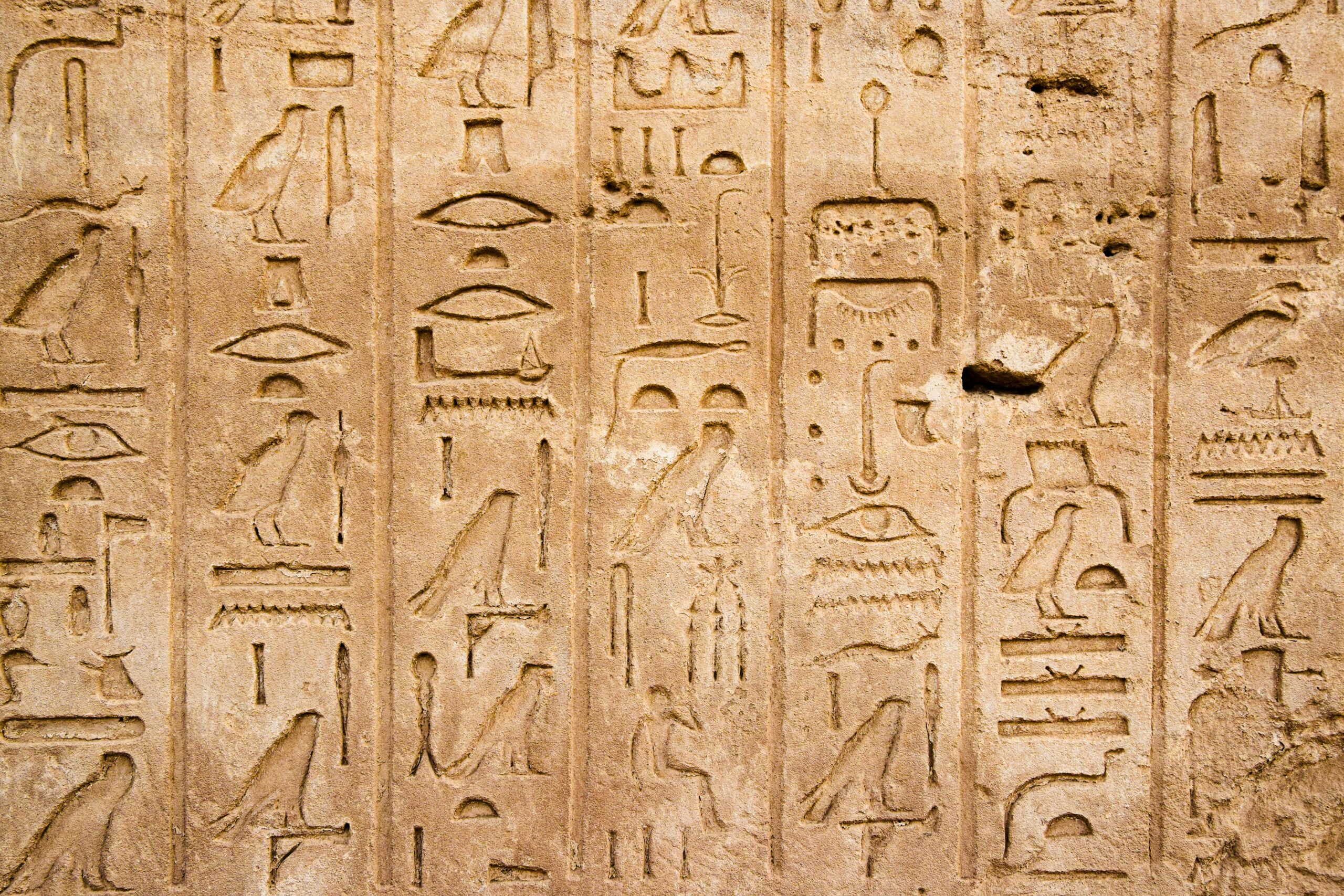

Long before the invention of writing as we know it, ancient humans developed intricate symbol systems that bridged the gap between simple imagery and complex language. These proto-writing systems represent humanity’s earliest attempts to externalize thought and memory.

The journey from prehistoric markings to sophisticated alphabets spans tens of thousands of years, revealing a fascinating cognitive evolution. Understanding these ancient symbol systems unlocks profound insights into how our ancestors perceived their world, organized societies, and transmitted knowledge across generations. Proto-writing represents not just historical curiosity, but a window into the very development of human consciousness and abstract thinking.

🗿 What Defines Proto-Writing Systems?

Proto-writing refers to mnemonic and symbolic systems that communicate information but lack the full linguistic structure of true writing. Unlike complete writing systems that can represent spoken language comprehensively, proto-writing serves as a transitional stage between pictorial representation and phonetic scripts.

These systems typically employ abstract symbols, pictographs, or ideograms to convey specific meanings, concepts, or serve as memory aids. The distinction between proto-writing and true writing remains debated among scholars, but most agree that proto-writing cannot fully represent grammatical structures or complex spoken utterances.

Key characteristics that distinguish proto-writing include the inability to express any thought that could be spoken, limited vocabulary of symbols, context-dependent interpretation, and primarily mnemonic rather than linguistic function. These systems represent humanity’s cognitive bridge toward more sophisticated communication technologies.

The Cognitive Leap: Why Did Symbols Emerge?

The development of symbolic thinking represents one of humanity’s most significant cognitive achievements. Archaeological evidence suggests that abstract symbol use emerged gradually, coinciding with other indicators of advanced cognition including sophisticated tool-making, ceremonial burial practices, and artistic expression.

Early humans faced increasing social complexity requiring methods to track resources, record astronomical observations, maintain ritual knowledge, and establish territorial claims. These practical needs likely drove the development of external symbolic systems that could persist beyond individual memory and oral tradition.

Neurological Foundations of Symbolic Thinking

Modern neuroscience reveals that symbolic representation requires specific cognitive capabilities including mental abstraction, categorization, pattern recognition, and the ability to assign arbitrary meaning to visual marks. The human brain’s unique capacity for symbolic thought likely co-evolved with language development, creating a feedback loop that accelerated both capabilities.

The archaeological record shows this cognitive revolution occurred between 100,000 and 40,000 years ago, though debate continues about precise timelines. Evidence includes ochre engravings in Blombos Cave, South Africa, dating to approximately 75,000 years ago, representing some of humanity’s earliest abstract markings.

🔍 Ancient Symbol Systems Around the World

Proto-writing systems emerged independently across different continents and cultures, each reflecting unique environmental, social, and cognitive contexts. Examining these diverse systems reveals universal patterns in how humans externalize thought while highlighting cultural specificity in symbolic expression.

European Cave Markings and Geometric Signs

Paleolithic cave art throughout Europe contains not only famous animal depictions but also mysterious geometric symbols appearing repeatedly across vast geographical distances. Researcher Genevieve von Petzinger catalogued 32 distinct geometric signs appearing in caves across Europe, spanning from 40,000 to 10,000 years ago.

These symbols include dots, lines, crosses, triangles, spirals, and more complex forms whose meanings remain largely enigmatic. Their repetition across thousands of years and miles suggests systematic meaning rather than random decoration. Some researchers propose these functioned as territorial markers, astronomical notations, or shamanic symbols linked to altered consciousness states.

African Rock Art Traditions

Africa hosts some of humanity’s oldest symbolic traditions, with rock art sites spanning from the Sahara to southern regions. The Blombos Cave ochre engravings feature cross-hatched patterns that appear deliberately structured rather than decorative, suggesting possible proto-writing functions.

Later African rock art traditions include the sophisticated symbolic systems of San peoples in southern Africa, whose paintings encode complex mythological, astronomical, and cultural information comprehensible to initiated community members but opaque to outsiders.

The Vinča Symbols of Southeastern Europe

The Vinča culture of southeastern Europe (circa 5500-4000 BCE) produced thousands of inscribed artifacts bearing abstract symbols. These Vinča symbols appear on pottery, figurines, and spindle whorls, displaying characteristics that some researchers argue represent true writing, though this remains controversial.

The symbols show remarkable consistency and appear in various combinations, suggesting systematic use. Whether these constituted accounting systems, ownership marks, or religious symbols continues to generate scholarly debate, but their systematic nature places them firmly within proto-writing discussions.

📊 Mesopotamian Tokens and Early Accounting

Perhaps the clearest proto-writing-to-writing transition appears in ancient Mesopotamia, where a token system evolved into cuneiform script over several millennia. This progression provides invaluable insights into how abstract symbol systems develop into full writing.

Beginning around 8000 BCE, Mesopotamian cultures used clay tokens of various shapes to represent commodities: cones for grain measures, spheres for quantities of grain, cylinders for animals. This three-dimensional accounting system served administrative needs in increasingly complex agricultural societies.

From Tokens to Impressions

By 3500 BCE, administrators began enclosing tokens in clay envelopes, then pressing tokens into the envelope’s surface before sealing to indicate contents. This innovation marked a crucial transition—two-dimensional symbols began replacing three-dimensional tokens.

Eventually, the impressions alone sufficed without actual tokens inside, and scribes began drawing symbol representations directly on clay tablets. By 3200 BCE, this system evolved into proto-cuneiform, and by 3000 BCE, into full cuneiform writing capable of representing spoken Sumerian language.

| Period | System | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| 8000-3500 BCE | Clay Tokens | 3D objects representing commodities and quantities |

| 3500-3200 BCE | Token Impressions | 2D impressions on clay envelopes and tablets |

| 3200-3000 BCE | Proto-Cuneiform | Drawn pictographic symbols with limited phonetic elements |

| 3000 BCE onward | Cuneiform Writing | Full writing system with phonetic, syllabic, and logographic elements |

Chinese Oracle Bone Precursors

Chinese writing’s origins trace back to Neolithic symbols appearing on pottery, jade, and bone artifacts dating to 6000 BCE. These early markings show geometric and pictographic elements that may represent proto-writing stages, though their meanings remain largely undeciphered.

The Jiahu symbols from Henan Province (circa 6600 BCE) appear on tortoise shells and represent some of China’s earliest potential proto-writing. While connections to later Chinese script remain speculative, they demonstrate early Chinese symbolic thinking traditions.

By the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BCE), fully developed Chinese writing appears on oracle bones used in divination rituals. The sophistication of these inscriptions suggests a long developmental period involving proto-writing stages that archaeological evidence is gradually revealing.

🌎 Mesoamerican Symbol Systems

The Americas developed independent symbolic traditions culminating in sophisticated writing systems. Mesoamerican cultures including the Olmec, Zapotec, and Maya created intricate symbol systems that encoded calendrical, astronomical, historical, and religious information.

Olmec symbols appearing around 1200-400 BCE show proto-writing characteristics including standardized glyphs that likely conveyed specific meanings. The Cascajal Block, discovered in 1999, contains 62 Olmec symbols in apparent sequence, though their meanings remain undeciphered.

Zapotec and Maya Developments

Zapotec writing, emerging around 500 BCE, represents Mesoamerica’s oldest confirmed writing system. Earlier symbolic systems from this region likely constituted proto-writing stages, gradually incorporating phonetic elements that transformed them into complete writing systems.

Maya script, fully developed by 300 CE, exhibits remarkable complexity with logographic and syllabic elements. Its evolutionary precursors demonstrate how proto-writing systems incrementally add linguistic specificity until achieving full writing capability.

Decoding the Undeciphered: Modern Approaches

Contemporary researchers employ multidisciplinary approaches combining archaeology, cognitive science, ethnography, statistics, and computational analysis to understand proto-writing systems. These methodologies reveal patterns invisible to traditional archaeological analysis alone.

Statistical analysis of symbol frequencies, positions, and combinations helps identify whether systems follow structured rules suggesting systematic meaning. Computational pattern recognition algorithms can detect subtle regularities across thousands of symbols that human observers might miss.

Ethnographic Analogies and Living Traditions

Studying contemporary non-literate societies that employ symbolic systems provides valuable analogies for understanding ancient proto-writing. Indigenous Australian message sticks, Native American winter counts, and African symbolic traditions demonstrate how sophisticated information can be encoded without full writing.

These living traditions remind researchers that proto-writing systems often functioned within rich oral contexts. The symbols served as memory triggers and mnemonic devices rather than standing alone, meaning their full significance may be archaeologically irrecoverable without cultural context.

💡 What Proto-Writing Reveals About Human Cognition

Proto-writing systems illuminate fundamental aspects of human cognitive evolution. They demonstrate that symbolic abstraction developed gradually through thousands of years rather than appearing suddenly. This gradual development suggests that biological and cultural evolution intertwined, each reinforcing the other.

The universal emergence of symbolic systems across isolated cultures indicates that certain cognitive thresholds, once reached, naturally express themselves through external symbol creation. This universality suggests deep neurological foundations for symbolic thinking in human brain architecture.

Memory Extension and Cultural Transmission

Proto-writing fundamentally transformed how cultures stored and transmitted information. Before external symbol systems, knowledge existed only in human memory and oral tradition, limiting societal complexity. Proto-writing enabled information persistence beyond individual lifespans and more reliable knowledge transmission across generations.

This cognitive technology allowed societies to accumulate complexity, maintain more elaborate ritual systems, track astronomical cycles accurately, and coordinate larger social groups. The archaeological correlation between proto-writing emergence and increasing social stratification suggests causal relationships between symbolic systems and societal organization.

The Threshold to True Writing

Understanding what transforms proto-writing into full writing systems remains crucial for appreciating human communicative evolution. The key transition involves incorporating phonetic representation—linking symbols to language sounds rather than just concepts or objects.

This phonetic principle allows unlimited expression matching spoken language capability. While proto-writing systems might employ hundreds of symbols each with specific meanings, phonetic writing can represent any utterance using relatively few symbols representing sounds or syllables.

Why Some Systems Crossed the Threshold

Only a handful of cultures independently developed full writing systems: Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, Mesoamerica, and possibly the Indus Valley. This rarity suggests that specific social, economic, and perhaps cognitive conditions must align for the proto-writing-to-writing transition.

Common factors among these cultures include urban development, complex administrative needs, specialized scribal classes, and sustained cultural continuity. These conditions provided both motivation and resources for developing increasingly sophisticated symbolic systems that eventually incorporated phonetic principles.

🔮 Modern Implications and Digital Parallels

Contemporary digital communication shows interesting parallels with ancient proto-writing. Emojis, icons, and visual symbols convey meaning outside traditional linguistic structures, functioning similarly to ancient symbolic systems. While supported by full literacy, digital symbols often communicate emotions and concepts more efficiently than words.

This return to symbolic communication in digital contexts suggests that visual symbol systems fulfill cognitive and communicative needs that alphabetic writing alone cannot address. Understanding ancient proto-writing may illuminate how modern humans naturally gravitate toward hybrid symbolic-linguistic communication systems.

Ongoing Mysteries and Future Research

Despite significant advances, numerous proto-writing systems remain enigmatic. The Indus Valley script, Rongorongo of Easter Island, and countless lesser-known symbolic traditions await decipherment. Each mysterious system potentially holds unique insights into human cognitive diversity and cultural expression.

Future research will likely employ increasingly sophisticated computational analysis, including machine learning algorithms that detect patterns across massive datasets. Interdisciplinary collaboration bringing together archaeologists, linguists, cognitive scientists, and indigenous knowledge holders offers the best prospect for unlocking remaining mysteries.

Additionally, new archaeological discoveries continuously emerge, potentially revealing earlier symbolic systems that push back the timeline of human abstract thinking. Sites in Indonesia, Africa, and other regions may yield evidence of proto-writing predating current known examples, fundamentally revising our understanding of cognitive evolution.

Preserving Fragile Evidence of Ancient Minds

Many proto-writing systems survive only in fragile material contexts—rock surfaces exposed to weathering, organic materials subject to decay, or artifacts threatened by development and looting. Documenting and preserving these irreplaceable records of human cognitive history represents urgent archaeological and cultural priorities.

Modern digital documentation technologies including 3D scanning, high-resolution photography, and virtual reality reconstruction enable unprecedented preservation and analysis opportunities. These technologies allow researchers worldwide to study artifacts without physical access while creating permanent records protecting against loss.

Indigenous communities often hold traditional knowledge about symbolic systems created by their ancestors. Respectful collaboration with these communities provides crucial context for interpreting ancient symbols while honoring cultural continuity and intellectual property rights of descendant populations.

Connecting Ancient Symbols to Modern Understanding

Proto-writing systems bridge vast temporal distances, connecting contemporary humans with ancestors separated by thousands of generations. These ancient marks represent some of humanity’s earliest preserved thoughts—abstract ideas externalized and made permanent.

When we examine geometric symbols in European caves, Mesopotamian clay tokens, or Mesoamerican glyphs, we encounter minds fundamentally like our own confronting similar challenges: how to remember, communicate, and transmit knowledge beyond individual limitations. Proto-writing represents humanity’s first technology for thinking beyond biological constraints.

This connection to ancient minds reminds us that writing—something modern humans take for granted—required millennia of cognitive and cultural evolution. Every time we write, we employ technologies and cognitive capacities that ancient humans painstakingly developed through countless generations of experimentation and innovation.

The study of proto-writing ultimately reveals that human communication exists on a continuum from gesture and speech through symbolic systems of increasing complexity toward full writing and beyond to digital communication. Understanding this continuum provides profound insights into what makes us human and how we became the symbolic, communicative species we are today. These ancient marks represent not mere historical curiosities but foundational technologies that enabled civilization itself, deserving continued study, preservation, and wonder.

Toni Santos is a cultural researcher and historical storyteller exploring the intersection of archaeology, design, and ancient innovation. Through his work, Toni examines how forgotten technologies and sacred geometries reveal humanity’s enduring creativity. Fascinated by the craftsmanship of early civilizations, he studies how symbolic architecture and prehistoric ingenuity continue to influence modern design and thought. Blending archaeology, art history, and cultural anthropology, Toni writes about rediscovering the wisdom embedded in ancient forms. His work is a tribute to: The ingenuity of ancient builders and inventors The mathematical harmony of sacred design The timeless curiosity that drives human innovation Whether you are passionate about archaeology, history, or cultural symbolism, Toni invites you to uncover the brilliance of the past — one artifact, one pattern, one story at a time.